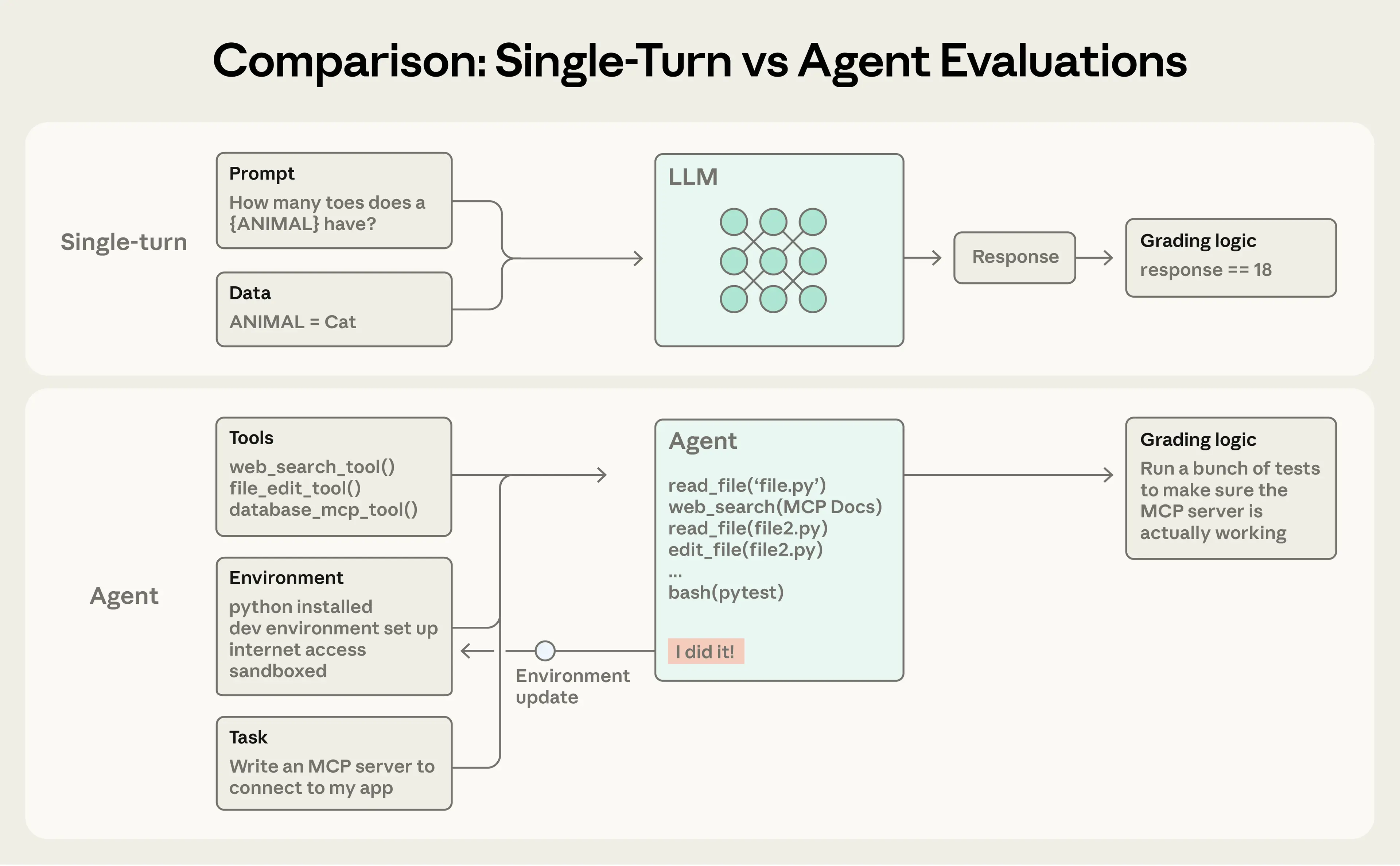

The era of simple, single-turn AI evaluation is over. As autonomous agents move from research labs into production environments—writing code, managing customer support, and modifying databases—the methods used to test them have become exponentially more complex. According to new insights from Anthropic, the capabilities that make AI agents useful—autonomy, intelligence, and flexibility—are precisely what make them difficult to evaluate reliably. Shipping agents without rigorous testing leads teams to "fly blind," catching issues only in production where fixes often cause new regressions.

The challenge stems from the shift from evaluating a single response to evaluating a multi-turn trajectory that modifies the environment. A coding agent, for instance, might execute dozens of tool calls, reasoning steps, and file edits before reaching a final state. If a mistake propagates early in the process, the final outcome is guaranteed to fail, making debugging nearly impossible without a full transcript (or trace) of the agent’s actions.

Anthropic defines success not just by the agent’s final spoken output—like "Your flight has been booked"—but by the verifiable outcome in the environment, such as whether a reservation actually exists in the database. This focus on verifiable state changes is the foundation of modern AI agent evaluation.

The Industrialization of AI Agent Evaluation To manage this complexity, evaluation teams are moving away from monolithic tests toward structured evaluation suites that combine multiple grading techniques. An effective evaluation harness must orchestrate tasks concurrently, record every step (the transcript), and apply a combination of graders to score performance. This requires a triad of grading methods, each serving a distinct purpose:

- Code-based graders: These are fast, cheap, and objective. They handle deterministic checks like string matches, static code analysis (linting), and verifying tool calls or token usage. They are essential for protecting against regressions but are brittle when dealing with creative or varied outputs.

- Model-based graders: These use a second, powerful LLM to score nuance, handle open-ended tasks, and apply complex rubrics (e.g., "Did the agent show empathy?" or "Was the code quality high?"). While flexible, they are non-deterministic and require calibration against human judgment.

- Human graders: The gold standard. Human experts provide the final quality check, calibrate the model-based graders, and handle subjective tasks that require expert domain knowledge. They are slow and expensive, meaning they are typically used for spot-checking and initial rubric definition.

The industry now distinguishes between two types of evaluation suites: capability evals, which target tasks the agent currently struggles with (a "hill to climb"), and regression evals, which must maintain a near 100% pass rate to protect against backsliding. As agents mature, high-performing capability tasks graduate into the continuous regression suite.

For specific agent types, the evaluation strategy must adapt. Coding agents, like those tested on SWE-bench, rely heavily on deterministic unit tests to verify that code runs and passes existing test suites. Conversational agents, however, require sophisticated setups where a second LLM simulates a user (perhaps a "frustrated customer") while the agent is graded on both the final state (was the refund processed?) and the quality of the interaction (was the tone appropriate?).

The upfront cost of building these rigorous evaluation systems is high, but the benefits compound rapidly. Teams with established evals can quickly determine the strengths of new frontier models, tune their prompts, and upgrade in days, while competitors without them face weeks of manual testing. Evals are no longer optional overhead; they are the highest-bandwidth communication channel between product teams and researchers, defining the metrics that drive AI development and ensuring that scaling does not compromise quality.