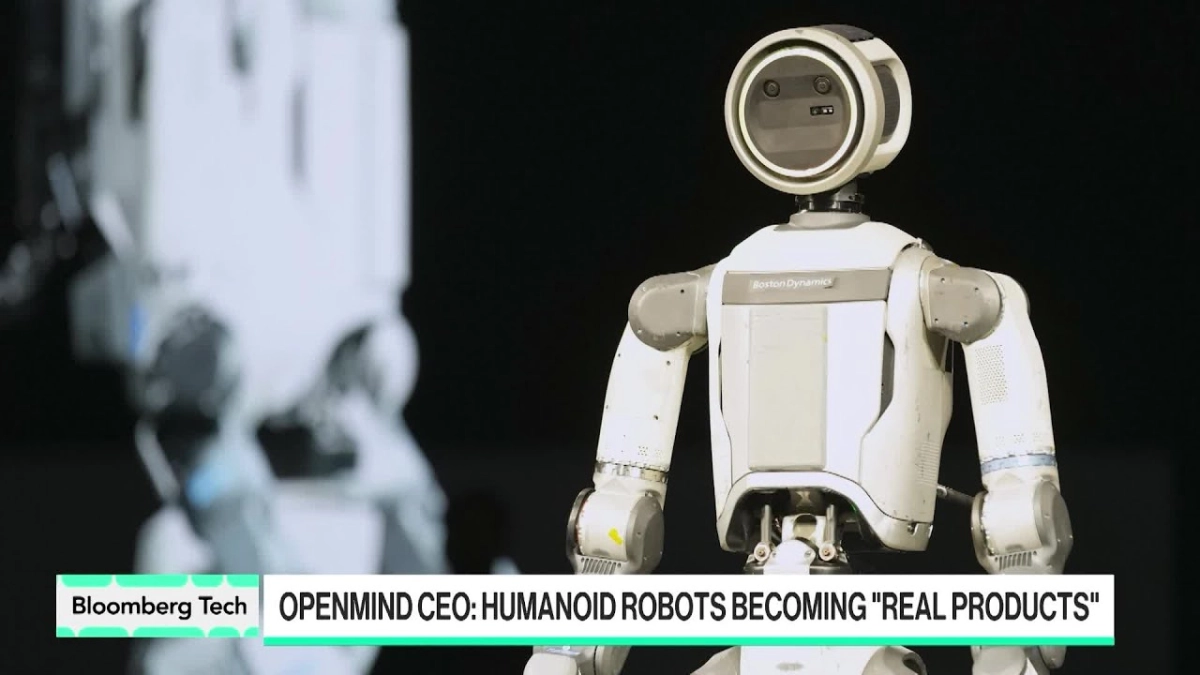

“Just a few years ago, the robots here were kind of janky,” observed Jan Liphardt, Founder and CEO of Openmind and a Stanford professor. This stark assessment, delivered during an interview at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES), encapsulates the dramatic shift occurring in the robotics sector: the transformation of wobbly academic prototypes into viable commercial products ready for deployment. The palpable excitement surrounding humanoids at the event, evidenced by two-hour queues just to see models like Boston Dynamics’ Atlas, signals that the industry is hitting a critical inflection point, moving from theoretical capability to market readiness.

Liphardt spoke with Bloomberg Tech anchors about the accelerating pace of humanoid robot development, noting that the conversation has shifted dramatically from mere mechanical feasibility to practical software application and market penetration. The consensus among technologists is that the fundamental problems of physical manipulation in structured environments have largely been overcome, paving the way for more complex, socially integrated applications. This transition challenges traditional paradigms in robotics development, demanding a new focus on adaptability and intelligence over raw mechanical prowess.

For industrial applications, the core logistical challenges—the "pick and place" problems common in warehouses and manufacturing—are already solved. Liphardt confirmed this reality, stating plainly that, “The logistics, pick and place is effectively solved,” citing Amazon’s massive deployment of 1.1 million non-humanoid robots as evidence of commercial maturity in structured environments. This industrial success sets the stage for the next frontier: the unstructured, unpredictable human world.

The special advantage of the humanoid form factor is its inherent compatibility with existing human infrastructure—door handles, light switches, and stairs. They can immediately be effective in spaces humans have already built.

The true challenge now lies in "social robotics," tasks that require nuanced interaction and adaptation within human spaces, whether that is in a home, a hospital, or a classroom. Unlike fixed industrial robots, humanoids must navigate and operate within environments designed for bipedal, two-armed beings. This is where the complexity of software—the ability to learn, adapt, and perform varied tasks—becomes the definitive bottleneck and competitive differentiator.

This shift has created a tension between the traditional hardware-centric robotics firms and the new wave of software-first companies. Many established humanoid robotics companies have historically focused on vertical integration, building both the physical platform and the proprietary control systems. However, Liphardt notes that many of these hardware-focused entities are now struggling to maintain the software frontier, creating an opening for platforms like Openmind. These platforms aim to decouple the software from the hardware, mirroring the cell phone model. “We think of them much more like cell phones… where developers everywhere can add apps or skills that will allow your humanoids to do many more things very quickly,” he explained, suggesting that the future value will be captured by those who build the most open and robust software ecosystems.

The most profound, if initially unsettling, use cases are emerging in the sphere of elder care and companionship. The shortage of human caregivers worldwide presents a massive addressable market, yet the application requires robots to fulfill deeply human, emotional needs. Liphardt shared heartbreaking stories from memory care facilities where "the patients will kiss the humanoid," illustrating a powerful, unexpected level of emotional attachment. This interaction, though potentially dystopian to some observers, highlights a profound human need for connection that technology is now capable of meeting, especially for those starved of human interaction. The robot’s utility in these scenarios transcends mere functional assistance; it provides companionship and engagement, demonstrating that the future of robotics is intrinsically linked to solving human loneliness and providing emotional care.

The debate over the optimal form factor—whether a humanoid or a specialized machine—remains secondary to the central challenge of intelligence and adaptability. However, the compatibility of the humanoid shape with existing infrastructure means that these devices are poised to be the first general-purpose robots to enter the mainstream. The next decade will be defined by which firms can successfully build the open software layer necessary to unlock the vast, unpredictable potential residing in these increasingly capable physical forms, moving beyond the factory floor into the complex, emotional ecosystem of human life.