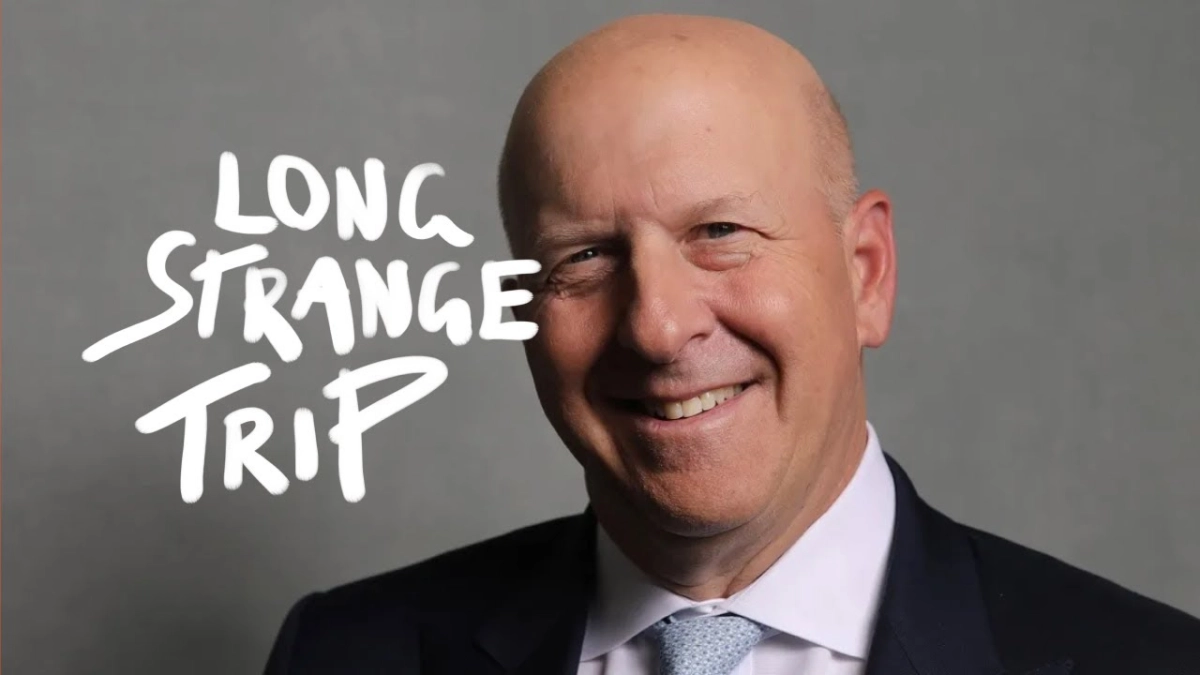

The modern landscape of leadership, particularly within the dynamic realm of AI and rapid technological advancement, often glorifies youth, raw intelligence, and the disruptive "slope" of potential. Yet, a recent conversation between Brian Halligan, co-founder of HubSpot and partner at Sequoia, and David Solomon, CEO of Goldman Sachs, offered a refreshing counter-narrative, grounding leadership in the enduring virtues of experience, empathy, and an adaptable, yet firm, organizational culture. Their discussion on the "Long Strange Trip" podcast provided a rare glimpse into the realities of helming a 155-year-old financial titan, contrasting sharply with the prevailing Silicon Valley wisdom.

Solomon began by framing the very essence of the CEO role: it is a constant navigation of "51/49 decisions," where clarity is rare and the path forward is often a choice "between two shitty options," as Halligan himself once described his HubSpot days. This inherent ambiguity demands a leader capable of making tough calls, even when they involve publicly scaling back ambitious ventures. Solomon's candid reflection on Goldman Sachs's decision to wind down its consumer banking aspirations, including a high-profile partnership with Apple, exemplifies this difficult reality. It was a strategic pivot, born not from a simple calculation, but from a complex assessment of regulatory environments, internal pressures, and the long-term focus of the institution.

Such decisions, Solomon argues, are rarely about sheer intellect alone. While Silicon Valley often prioritizes hiring for "slope"—the promise of rapid learning and future impact—Solomon champions the irreplaceable value of experience. "You can't teach experience. It matters when the bumps come," he asserts, highlighting that true leadership is forged in the crucible of past challenges and the wisdom gained from navigating unforeseen difficulties. He advocates for being "smart enough," a baseline intelligence complemented by a comprehensive suite of human elements: the ability to connect, resilience, determination, and a relentless striving for excellence.

Goldman Sachs's longevity, surviving over a century and a half of market upheavals, is attributed by Solomon to its distinctive, albeit constantly evolving, culture. He stresses the continuous effort required to define, reshape, and amplify what truly matters within an organization's ethos. This proactive cultural stewardship fosters an environment where trust with clients is paramount, a long-term view is ingrained, and "doing the right thing" is believed to ultimately lead to positive outcomes. Such deeply embedded values, cultivated over generations, offer a stark contrast to the often personality-driven, transient cultures of many startups, where the founder's vision can eclipse institutional memory.

Solomon’s personal journey to the CEO chair was not a direct, pre-ordained path, but rather an organic progression marked by continuous learning and a willingness to embrace diverse responsibilities. He did not aspire to the top job but found fulfillment in leading people within large organizations. He credits mentors like Lloyd Blankfein, an "incredible risk manager," and Hank Paulson, who instilled a sense of "compass" and the resilience to keep it "pointed North" amidst external pressures. These figures, through their distinct leadership styles, taught Solomon the importance of self-reflection, understanding one's strengths and weaknesses, and the humility to constantly strive for improvement.

The conversation also touched upon the growing trend of partnerships between agile startups and established giants. Solomon offers a pragmatic perspective: most partnerships between companies are inherently challenging, requiring "really good alignment of incentives" and a robust governance structure to mitigate friction. He notes that while Goldman Sachs did build a "terrific" product and service with Apple, the long-term strategic fit and the evolving regulatory landscape ultimately necessitated a shift. This underscores that even the most promising collaborations demand constant re-evaluation against core business objectives and external realities.

Ultimately, Solomon's message to aspiring leaders and founders is one of holistic development. To lead a large enterprise successfully, one must do a "lot of different things" and gain a broad spectrum of experience. This journey, he cautions, will inevitably involve falling on one's face "so many times." However, it is through these trials, coupled with an unwavering commitment to an organization's core values—particularly client-centricity—that true leadership emerges, capable of orchestrating complex organizations to not just survive, but to thrive over the long haul.