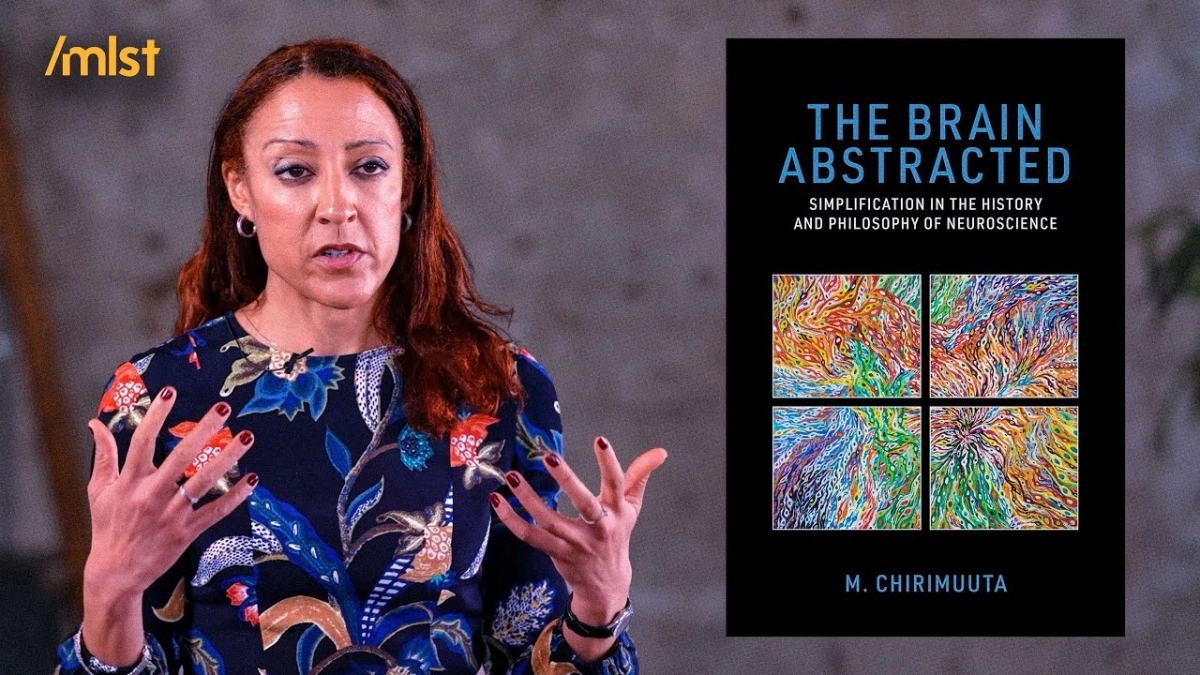

“We have the world of appearance. It's complicated. It looks intractable. It's messy. But underlying that, real reality is neat, mathematical, decomposable.” This statement, summarizing a persistent philosophical tension, cuts to the core of the challenge facing modern artificial intelligence. The current pursuit of strong AI is often underpinned by a Platonic idealism that risks repeating historical scientific errors by abstracting away the very biological complexity that defines human cognition. This was the sharp analysis provided by Professor Mazviita Chirimuuta, author of The Brain Abstracted, during a recent conversation with the host of the ML Street Talk podcast, where she discussed the philosophy of neuroscience, the limits of computational theories of mind, and the necessity of embodied knowledge.

Chirimuuta, whose background bridges neuroscience research and philosophy, frames the issue by distinguishing between necessary abstraction and dangerous idealization. Abstraction, she explains, is simply ignoring details irrelevant to a specific model—like ignoring air friction when calculating a simple Newtonian physics problem. Idealization, however, is attributing properties to a system that are known to be false, such as assuming infinite populations in genetics models. While useful for tractability, such idealizations can lead entire fields astray by creating "cleaner and better" theoretical constructs than the messy reality they purport to explain.

This critique is particularly relevant to the computational theory of mind (CTM) and the modern deep learning boom. Many AI researchers, Chirimuuta notes, subscribe to a Platonic belief—what AI expert François Chollet calls the "kaleidoscope effect." This is the idea that messy reality is merely a complex reflection, and that true underlying reality is a set of elegant, decomposable mathematical rules. The task of the scientist, then, is merely to "decompose back into the rules," believing that if a system’s external behavior can be modeled computationally, the underlying physical substrate is irrelevant.

This functionalist assumption, that the "brain is a computer," is the central philosophical pitfall. Chirimuuta highlights how this belief echoes past scientific failures, citing the cautionary tale of reflex theory in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Prestigious physiologists, including Charles Sherrington, invested heavily in the idea that all brain function could be reduced to simple, conditioned sensory-motor reflex arcs. Sherrington himself eventually admitted that the notion of a simple reflex was an idealization that likely "doesn’t exist in real life." Yet, the elegance of the theory led researchers to run with it "way too far," creating a theoretical cul-de-sac that failed to explain the full complexity of animal behavior. This history suggests that the current dominance of CTM may stem less from its ultimate truth and more from its intellectual convenience—it provides an idealization toolkit that allows scientists to bypass the overwhelming biological messiness.

The computational approach often embraces a behaviorist "black box" mentality, focusing only on inputs and outputs while ignoring the internal, causal mechanisms. But as Chirimuuta notes, drawing on John Searle’s famous thought experiments, computation itself lacks "causal powers." The real action—the capacity for understanding—lies in the physical implementation. The brain is not just a digital machine running abstract logic gates; it is a living, energy-constrained organ whose processes are fundamentally tied to its biological context. The signaling between neurons is intertwined with biochemical processes, vascularity, and immune system interactions—all factors disregarded by purely abstract computational models. Ignoring these specific, complex biological constraints makes it a massive stretch, Chirimuuta argues, "to say that a machine that’s not living could have the same functionality."

This brings the discussion to the concept of knowledge acquisition itself, contrasting the passive "spectator theory" with the active, embodied approach known as haptic realism. Haptic realism emphasizes that knowledge is constructed through active engagement and interaction—the sense of touch, manipulation, and physical intervention. This stands in stark contrast to the dominant visual metaphor of knowledge, where the knower is a passive observer reading off the "source code of the universe." Disembodied language models, which currently dominate the AI landscape, are rooted entirely in the spectator theory, relying on purely symbolic processing. Chirimuuta suggests that true intelligence—the kind that can navigate and understand the world—is deeply entangled with our sensory-motor engagement and biological existence.

Ultimately, the philosophical assumption that nature is fundamentally neat and mathematically parsable—a Platonic idealization—risks forcing scientific inquiry into convenient but ultimately limiting frameworks. While abstraction is a necessary tool for finite human (and artificial) minds, mistaking a useful abstraction for ultimate reality leads to scientific trajectories that fail to capture the protean, inexhaustibly complex nature of biological systems. The challenge for AI and neuroscience moving forward is to recognize that the most successful explanations may not be the most aesthetically elegant, but those that embrace the deep, causal entanglement between computation and its biological, embodied implementation.